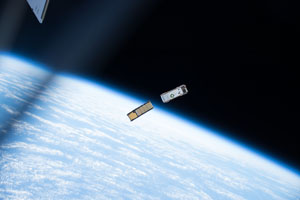

A bread-loaf-sized satellite has produced the world’s first map of the global distribution of atmospheric ice in the 883 GHz band, an important frequency in the submillimeter wavelength for studying cloud ice and its effect on Earth’s climate.

IceCube, the diminutive spacecraft that deployed from the International Space Station in May 2017, has demonstrated in space a commercial 883 GHz radiometer developed by Virginia Diodes Inc. (VDI) of Charlottesville, Va., under a NASA Small Business Innovative Research (SBIR) contract. The radiometer is capable of measuring critical atmospheric cloud ice properties at altitudes between three and nine miles (five and 15 km).

NASA scientists pioneered the use of submillimeter wavelength bands, which fall between microwave and infrared on the electromagnetic spectrum, to sense ice clouds. However, until IceCube, these instruments had only flown aboard high-altitude research aircraft. This meant scientists could gather data only in areas where the aircraft flew.

“With IceCube, scientists now have a working submillimeter radiometer system in space at a commercial price,” said Dong Wu, a scientist and IceCube principal investigator at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. “More importantly, it provides a global view on Earth’s cloud-ice distribution.”

Sensing atmospheric cloud ice requires scientists deploy instruments tuned to a broad range of frequency bands. However, it is particularly important to fly submillimeter sensors. This wavelength fills a significant data gap in the middle and upper troposphere, where ice clouds are often too opaque for infrared and visible sensors to penetrate. It also reveals data about the tiniest ice particles that can’t be detected clearly in other microwave bands.

The Technical Challenge

“IceCube’s map is a first of its kind and bodes well for future space-based observations of global ice clouds using submillimeter wave technology,” said Wu, whose team built the spacecraft using funding from NASA’s Earth Science Technology Office’s (ESTO) In-Space Validation of Earth Science Technologies (InVEST) program and NASA’s Science Mission Directorate CubeSat Initiative. The team’s challenge was making sure the commercial receiver was sensitive enough to detect and measure atmospheric cloud ice using as little power as possible.

Ultimately, the agency wants to infuse this type of receiver into an ice cloud imaging radiometer for NASA’s proposed Aerosol-Cloud-Ecosystems (ACE) mission. Recommended by the National Research Council, ACE would assess on a daily basis the global distribution of ice clouds, which affect the Earth’s emission of infrared energy into space and its reflection and absorption of the Sun’s energy over broad areas. Before IceCube, this value was highly uncertain.

“It speaks volumes that our scientists are doing science with a mission that primarily was supposed to demonstrate technology,” said Jared Lucey, one of IceCube’s instrument engineers. He was one of only a handful of scientists and engineers at Goddard and NASA’s Wallops Flight Facility in Virginia who developed IceCube in just two years. “We met our mission goals and now everything else is bonus,” he said.

Multiple Lessons Learned

In addition to demonstrating submillimeter wave observations from space, the team gained important insights into how to efficiently develop a CubeSat mission, determining which systems to make redundant and which tests to forgo because of limited funds and a short schedule, according to Jaime Esper, IceCube’s mission systems designer and technical project manager at Goddard.

“It wasn’t an easy task,” said Negar Ehsan, IceCube’s instrument system lead. “It was a low budget project” that required the team to develop both an engineering test unit and a flight model in a relatively short period of time. In spite of the challenges, the team delivered the VDI-provided instrument on time and budget.

“We demonstrated for the first time 883 GHz observations in space and proved that the VDI-provided system works appropriately,” she said. “It was rewarding.”

The team used commercial off-the-shelf components, including VDI’s radiometer. The components came from multiple commercial providers and did not always work together harmoniously, requiring engineering. The team not only integrated the radiometer to the spacecraft, but also built spacecraft ground-support systems and conducted thermal vacuum, vibration and antenna testing at Goddard and Wallops.

“IceCube isn’t perfect,” Wu conceded, referring to noise or slight errors in the radiometer’s data. “However, we can make a scientifically useful measurement. We came away with a lot of lessons learned from this CubeSat project, and next time engineers can build it much more quickly.”

“This is a different mission model for NASA,” Wu continued. “Our principal goal was to show this small mission could be done. The question was, could we get useful science and advance space technology with a low-cost CubeSat developed under an effective government-commercial partnership. I believe the answer is yes.”

Small satellites, including CubeSats, are playing an increasingly larger role in exploration, technology demonstration, scientific research and educational investigations at NASA, including: planetary space exploration, Earth observations, fundamental Earth and space science and developing precursor science instruments like cutting-edge laser communications, satellite-to-satellite communications and autonomous movement capabilities.

NASA ESTO supports InVEST missions like IceCube and technologies at NASA centers, industry and academia to develop, refine and demonstrate new methods for observing Earth from space, from information systems to new components and instruments.